Saturn’s Moon Shows Signs of Habitability

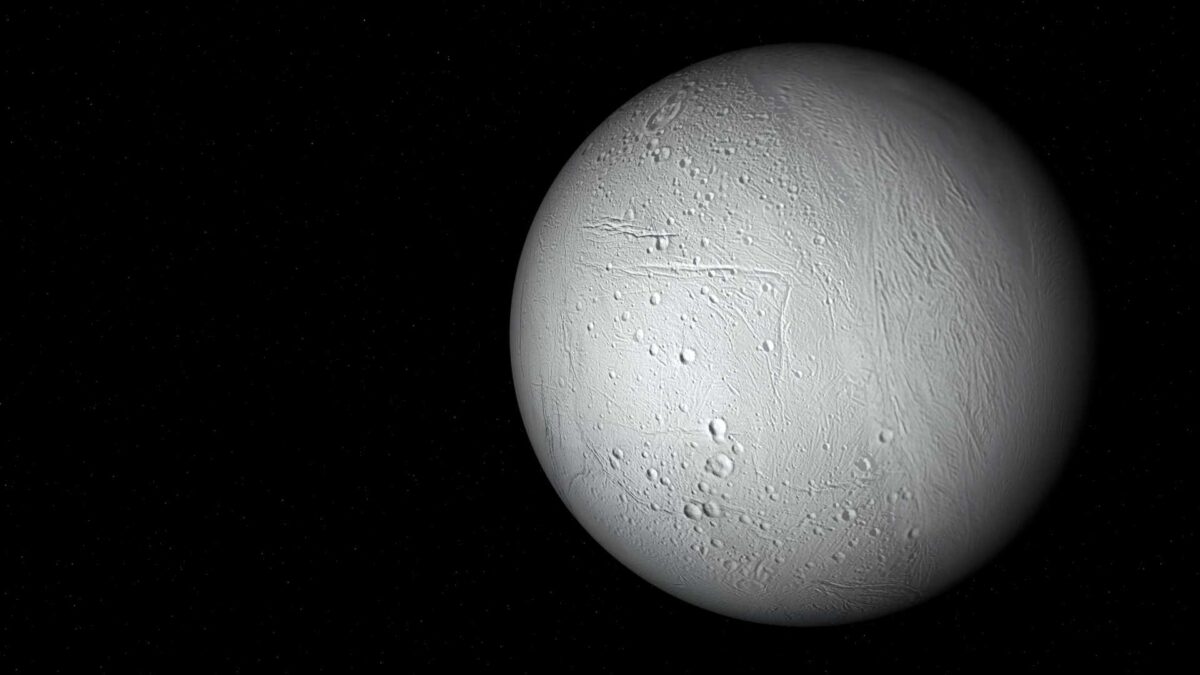

Saturn’s icy moon Enceladus is showing signs of being more hospitable to life than previously thought, according to new findings published in Science Advances.

The study, led by researchers from Oxford University, the Southwest Research Institute and the Planetary Science Institute in Arizona, reveals that the moon is losing heat from both its poles, not just the south as earlier believed.

This discovery strengthens the case that Enceladus could support life. The moon is known to have a global subsurface ocean beneath its frozen crust. For life to develop, that ocean must remain stable over long periods. The new research suggests that the balance between heat generated by tidal forces from Saturn and the heat lost into space is close to even. This balance would allow the ocean to stay liquid for millions of years.

Until now, scientists had only measured heat escaping from the south pole, where plumes of water vapour and ice erupt from surface cracks. The north pole was thought to be geologically quiet. However, by comparing infrared data from NASA’s Cassini spacecraft taken during the moon’s winter in 2005 and summer in 2015, researchers found that the north pole was warmer than expected. The only explanation, they say, is that heat is leaking from the ocean below.

The study estimates that the north pole is losing about 46 milliwatts of heat per square metre. While that may sound small, it adds up to around 35 gigawatts across the moon’s surface. When combined with the heat escaping from the south pole, the total reaches 54 gigawatts. This figure closely matches the amount of heat predicted to be generated by tidal forces.

The findings also offer new insights into the thickness of Enceladus’ ice shell. Using thermal data, the team estimated the ice is between 20 and 23 kilometres thick at the north pole and around 25 to 28 kilometres on average globally. These figures are slightly higher than previous estimates.

Dr Georgina Miles, lead author of the study, said the results highlight the importance of long-term missions. “Our study shows that data collected years ago can still reveal new secrets,” she said. “Understanding how much heat Enceladus is losing is key to knowing whether it can support life.”

The next step for researchers is to determine how long Enceladus’ ocean has existed. Its age remains uncertain but will be crucial in assessing whether life had enough time to emerge. The findings will also help guide future missions that aim to explore the moon’s ocean using robotic landers or submersibles.

Share this WeathÉire story: