New Webb image sheds light on how planets are born

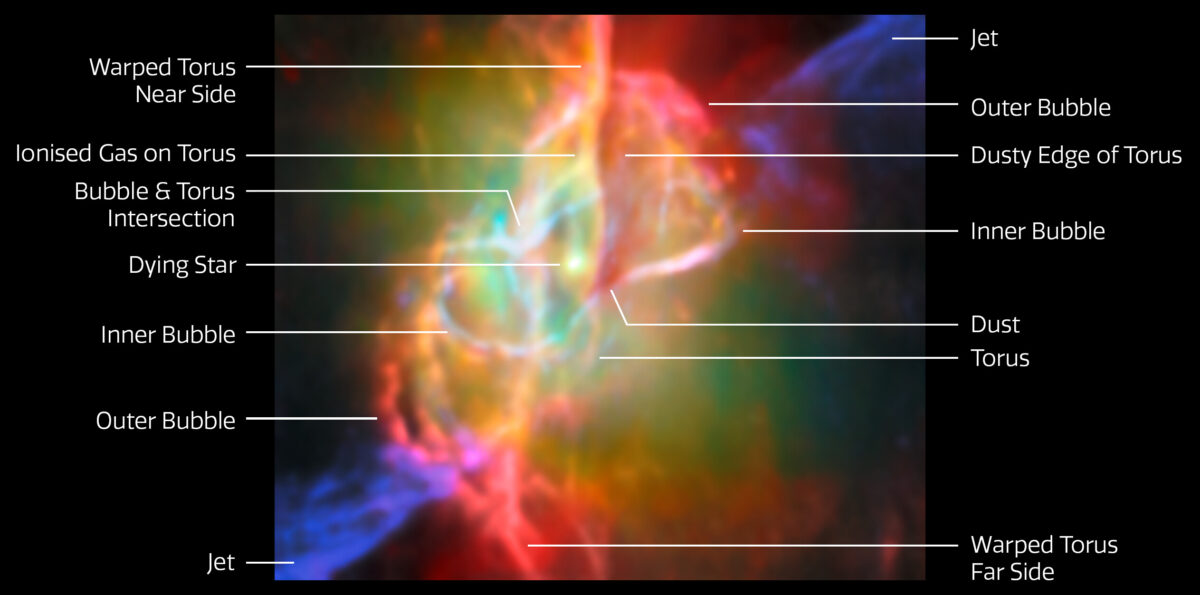

Clues to how planets such as Earth may have formed have been uncovered in the core of the Butterfly Nebula, one of the most striking planetary nebulae in the Milky Way.

Using the James Webb Space Telescope, an international team of researchers studied cosmic dust within the nebula, which lies about 3,400 light-years away in the constellation Scorpius. The findings, published in Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, reveal how the raw material of rocky planets comes together in space.

The Webb data show that the dense torus of gas and dust surrounding the nebula’s central star contains crystalline silicates, such as quartz, alongside irregularly shaped grains. The particles are relatively large for cosmic dust, suggesting they have been growing for a long time.

Most cosmic dust is amorphous, like soot, but the Webb observations found both crystalline “gemstone-like” grains formed in calm regions and amorphous dust produced in more turbulent areas.

Lead researcher Dr Mikako Matsuura of Cardiff University said the discovery provides a clearer picture of how the basic building blocks of planets emerge. “We were able to see both cool gemstones formed in calm, long-lasting zones and fiery grime created in violent, fast-moving parts of space, all within a single object,” she said.

The central star of the Butterfly Nebula is one of the hottest of its kind, with a temperature of 220,000 Kelvin. Its intense radiation powers the nebula’s glow, while the torus channels the flow of gas and dust, helping to shape its distinctive “wings”.

The researchers also detected carbon-based molecules known as polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in the nebula. On Earth, PAHs are commonly found in smoke and exhaust fumes. Their presence in this oxygen-rich environment may represent the first evidence of such molecules forming in a planetary nebula of this type.

The Butterfly Nebula, also catalogued as NGC 6302, has been extensively studied with both ground- and space-based telescopes. Planetary nebulae are formed when Sun-like stars shed their outer layers near the end of their lives, a process lasting only about 20,000 years. Despite their name, planetary nebulae are not related to planets.

The Webb observations, supplemented with data from the Atacama Large Millimetre/submillimetre Array in Chile, identified nearly 200 spectral lines that reveal the distribution of atoms and molecules across the nebula. The analysis also enabled researchers to pinpoint the long-hidden central star, obscured until now by surrounding dust.

The new results provide the most detailed portrait yet of the Butterfly Nebula’s complex structure and the processes that govern the formation of cosmic dust, a key ingredient in the creation of new planets.

Share this WeathÉire story: