Fewer aerosols, faster warming, study warns

Earth is reflecting less sunlight and absorbing more heat than several decades ago, pushing global warming ahead of previous projections, according to a new study.

Published on Wednesday in Nature Communications, the research shows that efforts to reduce air pollution have inadvertently dimmed the brightness of marine clouds, which play a crucial role in regulating global temperature.

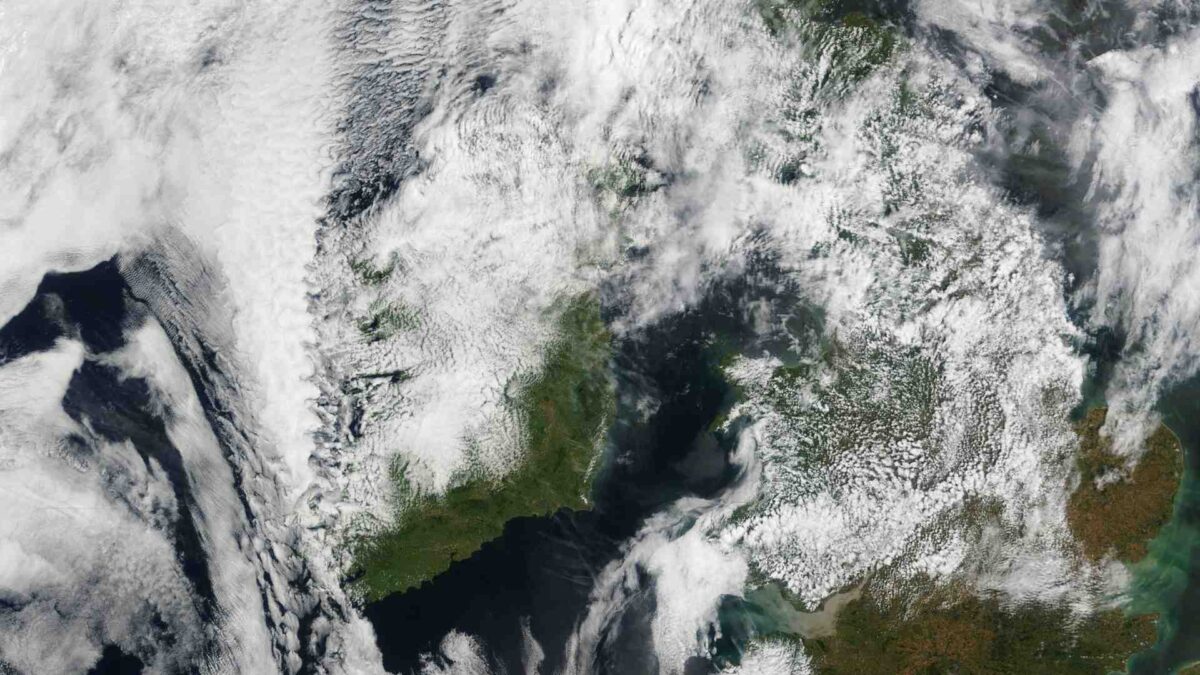

Between 2003 and 2022, clouds over the Northeastern Pacific and Atlantic oceans became nearly 3 per cent less reflective per decade. Scientists attribute around 70 per cent of this change to aerosols, tiny particles in the atmosphere that both influence cloud formation and block sunlight.

The reduction of aerosols, which comes as governments worldwide limit fossil fuel emissions, has led to fewer and larger cloud droplets. Larger droplets fall more quickly as precipitation, shortening cloud lifespans and reducing the clouds’ cooling effect.

Sarah Doherty, a principal research scientist at the University of Washington, said the study provides strong evidence that reductions in particulate air pollutants are accelerating warming. “It is clearly a good thing that we have been reducing particle pollution in the atmosphere. We do not want to go back in time and take away the Clean Air Act,” she said, referencing the 1963 US legislation that inspired similar regulations worldwide.

Lead author Knut von Salzen, a senior research scientist in atmospheric and climate science at the University of Washington, said the findings show that current climate models may underestimate warming trends. “When you cut pollution, you are losing reflectivity and warming the system by allowing more solar radiation to reach Earth,” he explained.

The Northeastern Pacific and Atlantic are among the fastest-warming regions on the planet, threatening fisheries and marine ecosystems. The researchers analysed 20 years of satellite data to track changes in cloud reflectivity and identify the role of aerosols in cloud dynamics.

The study also raises the possibility of interventions to restore cloud brightness without polluting the atmosphere. One proposed method, marine cloud brightening, involves spraying seawater into the air to make low-lying oceanic clouds more reflective. However, scientists stress that further research is needed to ensure such approaches are safe and free from unintended effects.

The research team includes scientists from the University of Toronto, Imperial College London and Environment and Climate Change Canada. Funding was provided by the University of Washington Marine Cloud Brightening Research Program, Environment and Climate Change Canada, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), and several UK and Canadian research fellowships.

Share this WeathÉire story: