Sun’s secret storms: scientists spot new space weather danger

Swirling spirals of solar wind can spin off from major eruptions on the sun and disrupt Earth’s magnetic field, but they are too small to detect with today’s warning systems, a new study from the University of Michigan has found.

Researchers say a fleet of spacecraft, including one powered by sunlight, could spot these tornado-like structures early enough to protect satellites, aircraft and power grids from disruption.

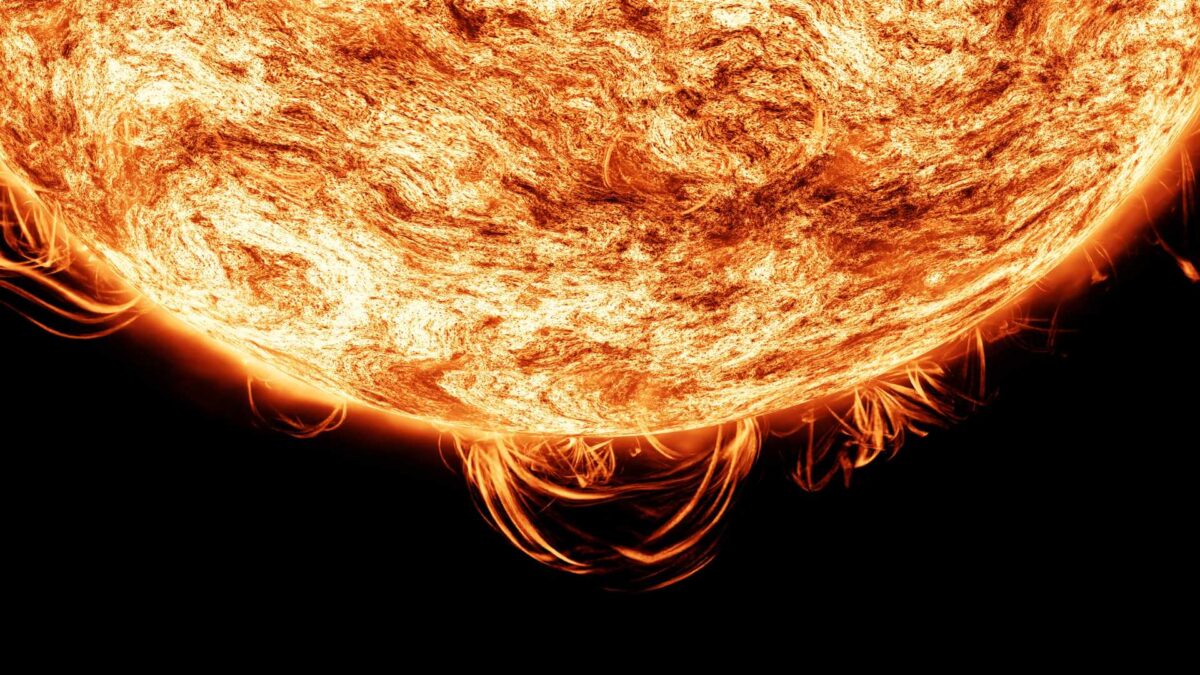

The findings come from advanced computer simulations showing how small, twisting bundles of plasma and magnetic field, known as flux ropes, form within larger solar eruptions. These miniature solar tornadoes can be powerful enough to trigger geomagnetic storms that affect technology on Earth.

“Our simulation shows that the magnetic field in these vortices can be strong enough to trigger a geomagnetic storm and cause some real trouble,” said Chip Manchester, research professor at the University of Michigan and lead author of the study, published in The Astrophysical Journal.

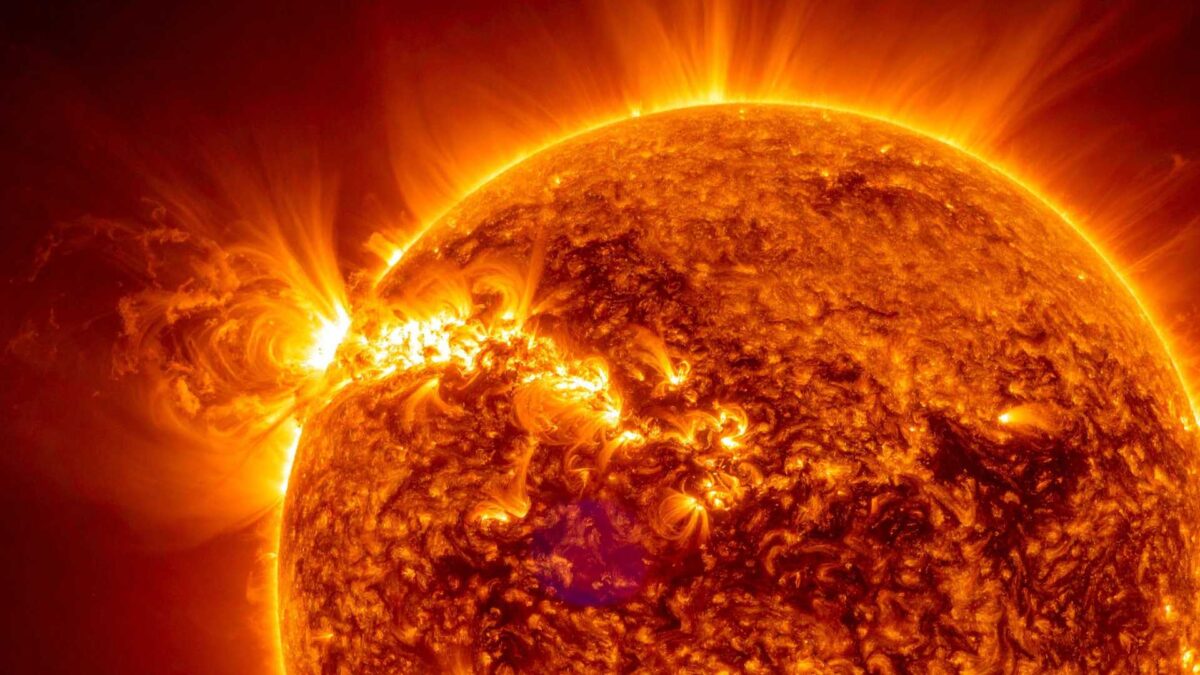

Geomagnetic storms can knock out communications and navigation systems, damage power lines and disrupt satellite operations. In May 2024, one such storm forced planes to change course, knocked satellites off track and scrambled GPS signals used by farm machinery in the United States. NASA estimated the average loss at $17,000 per farm.

The research, funded by NASA and the National Science Foundation, focuses on improving forecasting of these events, which are driven by the solar wind, a stream of charged particles that constantly flows from the sun. When the sun releases a coronal mass ejection, a giant bubble of plasma, it can drive extreme space weather across the solar system.

The new Michigan study shows that as these massive eruptions plough through slower solar wind, they can fling off smaller spinning structures like a snowplough tossing snow. Some of these spirals fade quickly, but others persist and can collide with neighbouring streams, creating long-lived plasma tornadoes.

“If there are hazards forming out in space between the sun and Earth, we can’t just look at the sun,” said co-author Mojtaba Akhavan-Tafti, associate research scientist at Michigan. “We need to find and track these flux ropes before they reach Earth so we can give grid operators, airlines and farmers proper warnings.”

At present, space weather warnings rely on measurements from a single point between Earth and the sun known as L1. But solar tornadoes that form outside this narrow line of sight could go undetected.

“Imagine trying to track a hurricane with one weather station,” Manchester said. “You’d see something change, but not the whole storm. That’s our current problem with space weather.”

To fix that, the team is proposing a new mission called the Space Weather Investigation Frontier, or SWIFT. It would use four small spacecraft arranged in a pyramid formation, each about 200,000 miles apart. Three would orbit near L1, while a fourth “hub” craft, positioned closer to the sun, would give warnings up to 40 per cent faster.

The outer probe would use a reflective aluminium sail about a third the size of a football field, designed to catch sunlight and hold its position without fuel. The concept builds on NASA’s Solar Cruiser technology.

If approved, SWIFT could give scientists the first 3D view of how solar storms evolve, and provide Earth with crucial extra minutes of warning when the next space tornado heads our way.

Share this WeathÉire story: