Marine life thriving on WW2 munitions

More marine life is thriving on World War II munitions dumped on the seabed of the Baltic Sea than in the surrounding sediment, according to new research.

The findings suggest that even highly toxic human debris can act as a habitat for marine organisms if it provides a hard surface to live on.

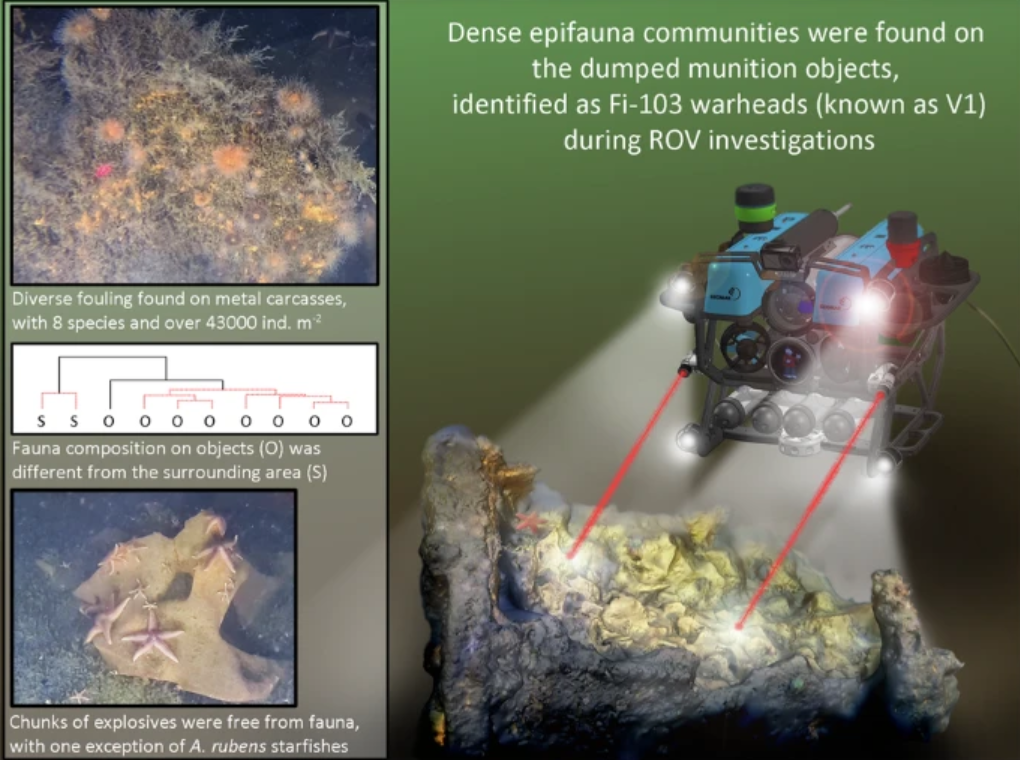

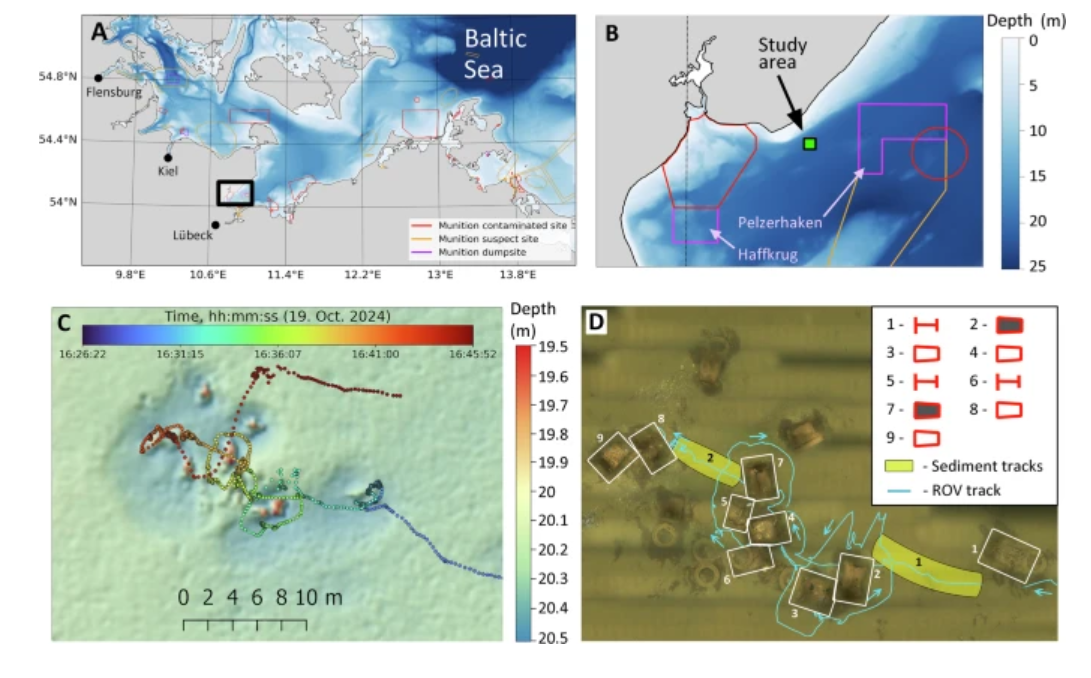

The study, published in Communications Earth & Environment, examined a newly-discovered munitions dumpsite in Lübeck Bay, Germany. Using a remotely operated submersible, Andrey Vedenin and colleagues filmed warheads from V-1 flying bombs – an early cruise missile used by Nazi Germany – and analysed water samples taken at the site in October 2024.

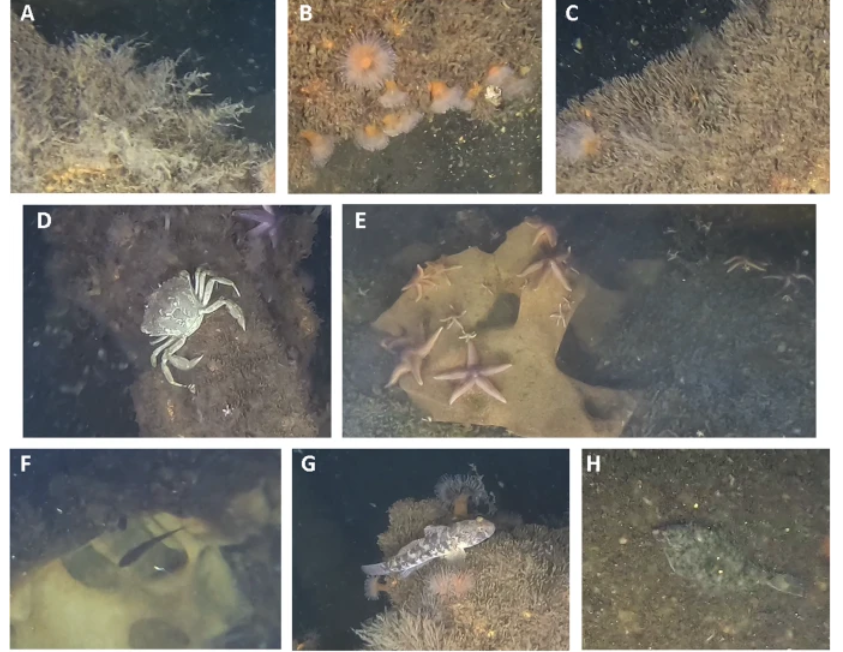

They found an average of 43,000 organisms per square metre living on the munitions, compared with about 8,200 organisms per square metre in the nearby sediment. Similar levels of abundance have been recorded on natural hard surfaces in the bay in other studies.

While concentrations of explosive compounds such as TNT and RDX varied from 30 nanograms per litre to 2.7 milligrams per litre – a potentially fatal level for marine life – the authors say the benefits of the hard surface appear to outweigh the dangers of chemical exposure. Most organisms were observed on the metal casings rather than uncovered explosive material, which may reflect efforts to limit exposure to toxins.

Before the 1972 London Convention on the Prevention of Marine Pollution, it was common practice to dump unused munitions at sea. Although the chemicals they contain are highly toxic, their casings can provide structure in otherwise soft or featureless seabeds. The researchers suggest that replacing the decaying munitions with safe artificial structures would further benefit local ecosystems.

A separate study published in Scientific Data highlights a similar phenomenon in the United States. David Johnston and colleagues have created a high-resolution photographic map of the 147 wrecks in the so-called “Ghost Fleet” of Mallows Bay on the Potomac River in Maryland.

The ships, built during World War I and scuttled in the late 1920s, are now an important habitat for species such as ospreys and Atlantic sturgeon. The team used aerial drones to capture photographs at an average resolution of 3.5 centimetres per pixel, producing a resource for future archaeological, ecological and cultural research.