Sharks may lose diversity after millions of years of evolution

Global shark populations risk losing much of their variety if current extinction trends continue, according to new research led by Stanford University.

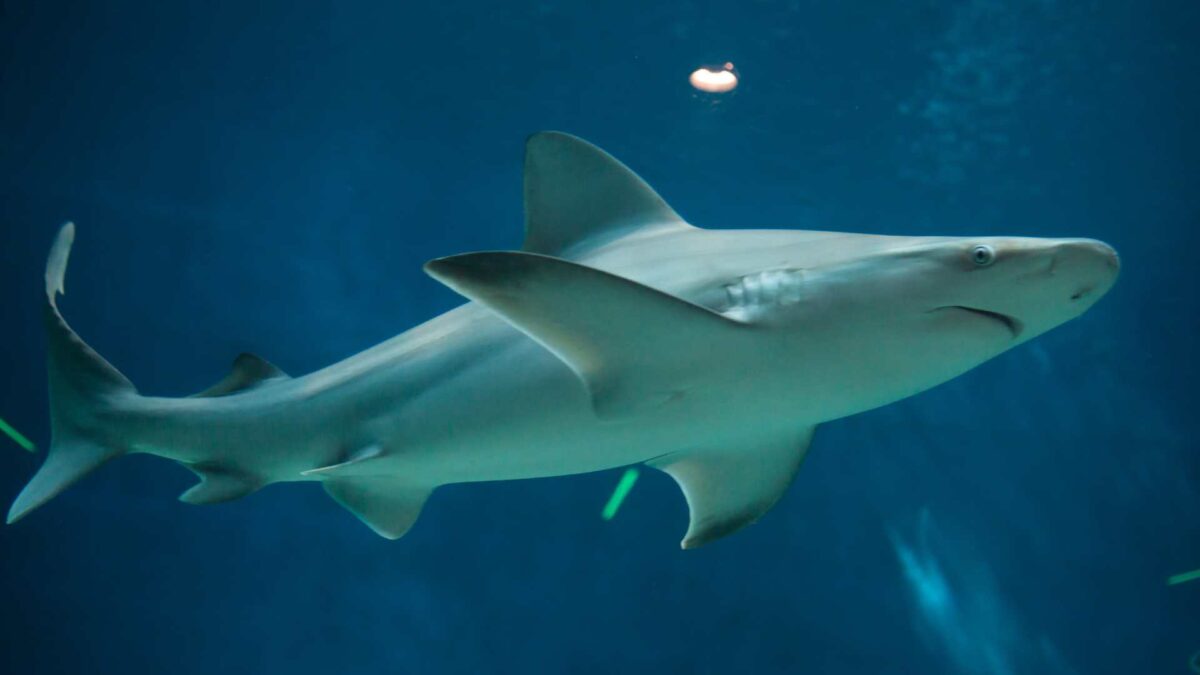

Having prowled Earth’s oceans for more than 400 million years, sharks have evolved into one of the planet’s most diverse animal groups. They range from palm-sized dwarf lanternsharks to whale sharks as long as a school bus. Yet a third of the world’s 500 shark species are now considered at risk of extinction, largely due to human activity.

The Stanford-led analysis found that the most threatened sharks tend to have unusual body shapes or highly specialised habitats, including species that live near the surface or in the ocean’s deepest zones. If such species vanish, the variety of shark forms and ecological roles would narrow to a smaller group of medium-sized, mid-depth generalists.

“Our study shows that if these extinctions occur, sharks will become more alike and simplified, and you end up with a less diverse world,” said lead author Mohamad Bazzi of the Stanford Doerr School of Sustainability.

Using thousands of fossil and modern teeth from 30 species in the shark genus Carcharhinus, researchers found that distinctive traits often correlate with higher extinction risk. Larger sharks and those with specialised diets are particularly vulnerable. The study suggests that extinction pressure promotes what scientists call “phenotypic homogenisation”, where species become increasingly similar in form and behaviour.

Senior author Professor Jonathan Payne said the disappearance of unique shark types would strip ecosystems of crucial functions. “Those popular shark books for kids would become a lot less fun and interesting,” he said.

The researchers warned that overfishing remains the single biggest driver of shark decline, but said the trend could be reversed through tighter laws, stronger enforcement and consumer restraint.

They pointed to the recovery of northern elephant seals as an encouraging example. Once hunted to near extinction for their blubber, the species rebounded to around 150,000 individuals after protection laws were introduced.

“People don’t need to think of conservation as something theoretical,” said Payne. “Within a few decades, some of these threatened shark populations could show real improvement.”

Share this WeathÉire story: