Astronomers Spot Planet in the Act of Forming

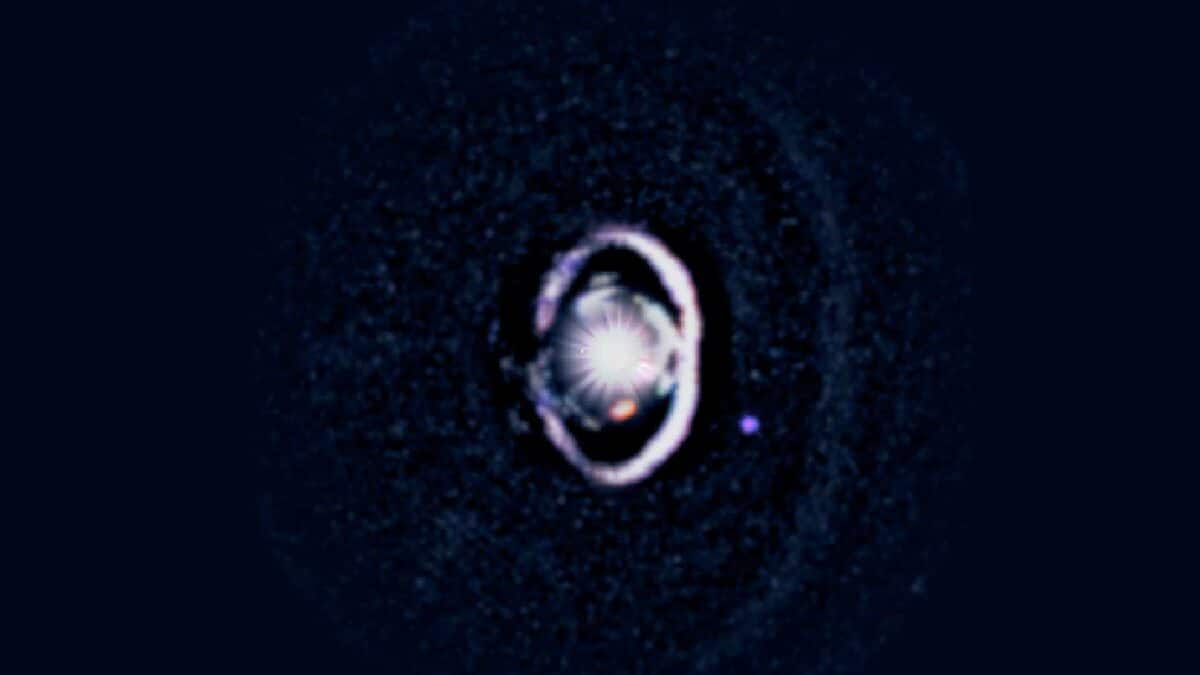

Astronomers have, for the first time, detected a planet actively forming in a gap of a multi-ringed disk of dust and gas around a young star, offering an unprecedented glimpse into the early stages of planetary formation.

The discovery was led by University of Arizona astronomer Laird Close and Richelle van Capelleveen, a graduate student at Leiden Observatory in the Netherlands. Using the University of Arizona’s MagAO-X extreme adaptive optics system at the Magellan Telescope in Chile, alongside observations from the Large Binocular Telescope in Arizona and the Very Large Telescope in Chile, the team published their results in The Astrophysical Journal Letters.

Astronomers have long studied planet-forming disks surrounding young stars. Many of these disks display gaps in their rings, suggesting they may be cleared by nascent planets. Until now, however, only a handful of growing protoplanets had been directly observed, and none had been found in these distinctive dark gaps.

“Dozens of theory papers have suggested these gaps are caused by protoplanets, but no one had found a definitive example until now,” Close said. He described the find as a “big deal,” as it confirms that protoplanets can indeed carve out the rings observed in many young star systems.

The newly discovered planet, named WISPIT 2b, orbits a star similar in mass to the Sun. A second candidate planet, CC1, was observed closer to the star. WISPIT 2b, estimated to be about five times the mass of Jupiter, occupies a gap approximately 56 times the distance from the Earth to the Sun, comparable to the outer edge of the Kuiper Belt in our solar system. CC1 is about nine Jupiter masses and sits closer to the star.

The team relied on H-alpha light, a specific emission produced when hydrogen gas falls onto a forming planet. MagAO-X, one of the most advanced adaptive optics systems in the world, allowed the astronomers to isolate the faint protoplanetary light from the overwhelming glare of the host star.

“It is a bit like looking at a baby picture of our own solar system 4.5 billion years ago,” said graduate student Gabriel Weible. “These planets are about ten times more massive than Jupiter and Saturn, but the system structure is reminiscent of what our solar system may have looked like in its infancy.”

Van Capelleveen, who led a parallel study using infrared observations from the Very Large Telescope in Chile, highlighted the rarity of witnessing planets in this fleeting stage. “Young disk systems are bright enough to be detected, but they only remain this way for a brief period,” she said.

The discovery sheds new light on how planets form and evolve, providing astronomers with a rare opportunity to study the processes that shaped our own solar system. Funding for the research came from NASA’s Exoplanet Research Program, the U.S. National Science Foundation, and the Heising-Simons Foundation.

Share this WeathÉire story: